In this section, you can learn more about knee cap pain by scrolling down the page.

You can also click on the links to the left to quickly access answers to common questions about your knee cap pain.

If you are a runner, we have a specific section for you here.

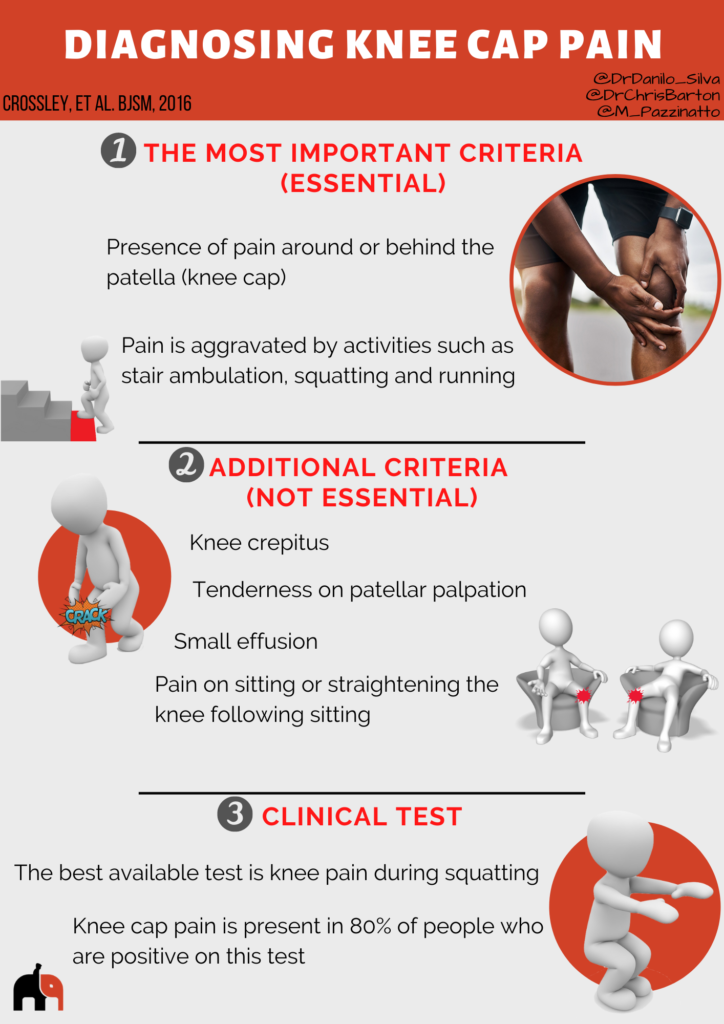

Diagnosis of your knee cap pain will most likely be termed patellofemoral pain, and should be provided by a suitably qualified health professional. Other common terms include chondromalacia patellae and runners knee.

This infographic does not replace consultation with a physiotherapist or doctor, but it might help you to understand if you have knee cap pain (patellofemoral pain).

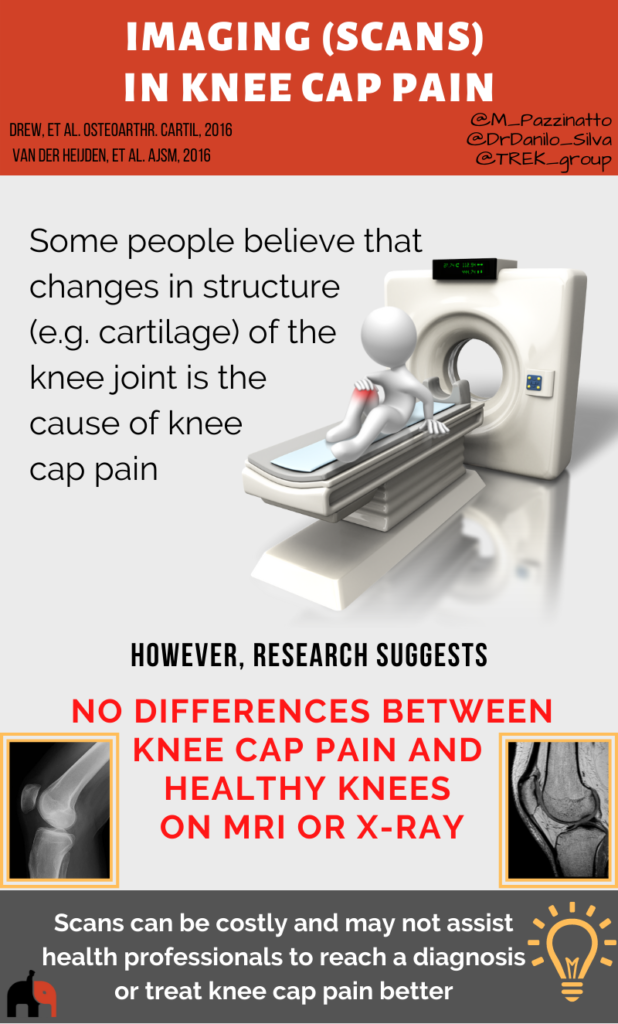

Imaging (Scans)

Some people believe that changes in structure (e.g. cartilage) of the knee joint is the cause of knee cap pain. However, research suggests no difference between people with knee cap pain and people without pain on MRI and X-ray. Therefore, imaging is not likely to help with knee cap pain diagnosis, or in determining appropriate treatments.

Supporting articles

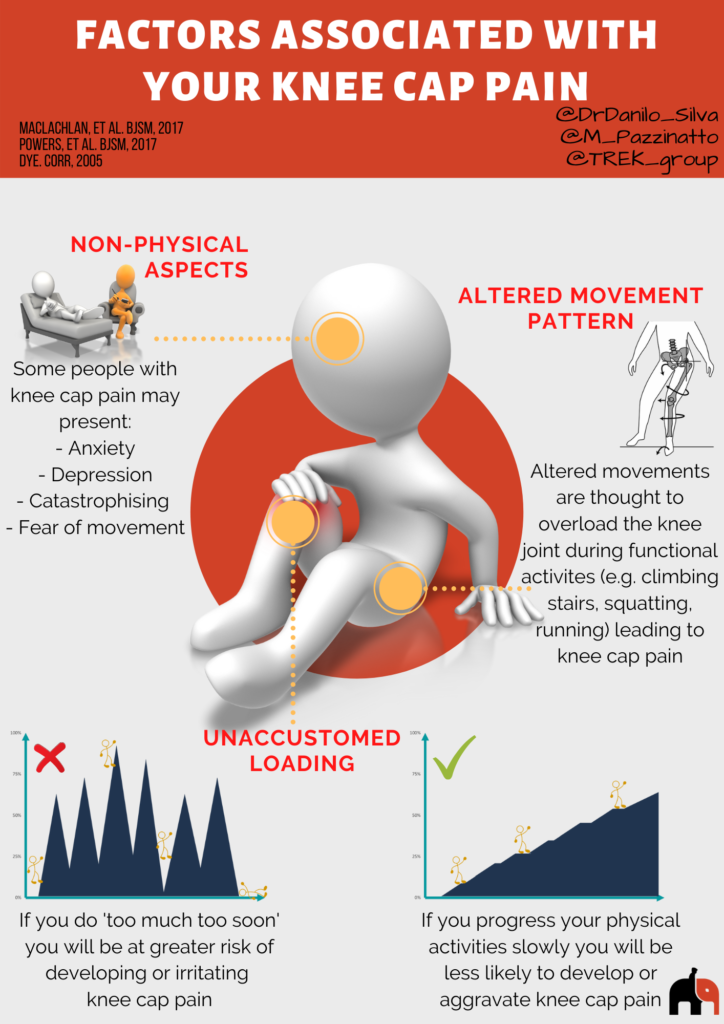

The factors that cause your knee to hurt are complex, and despite a lot of research are currently not completely clear. However, the infographic below helps to explain the most likely reasons.

Supporting articles

Dye 2005. The pathophysiology of patellofemoral pain: a tissue homeostasis perspective.

Maclachlan 2017. The psychological features of patellofemoral pain: a systematic review.

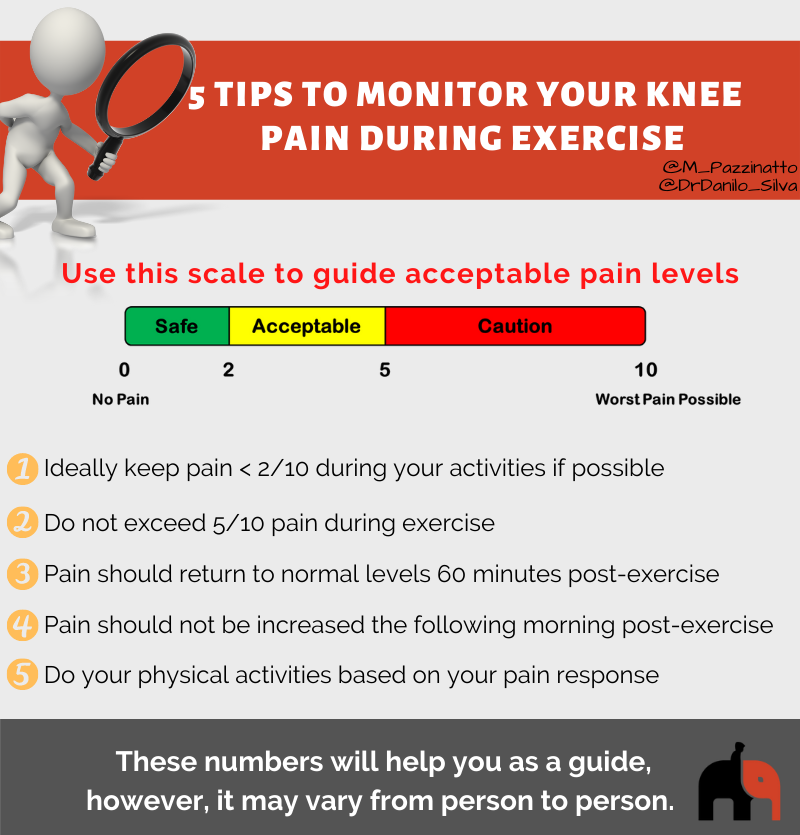

It is common for you to have knee cap pain at the beginning of your treatment. However, your pain should not achieve high levels in any physical activity you perform. That’s why we are providing 5 tips for you manage your knee cap pain during physical activities.

Use this infographic to guide acceptable pain levels:

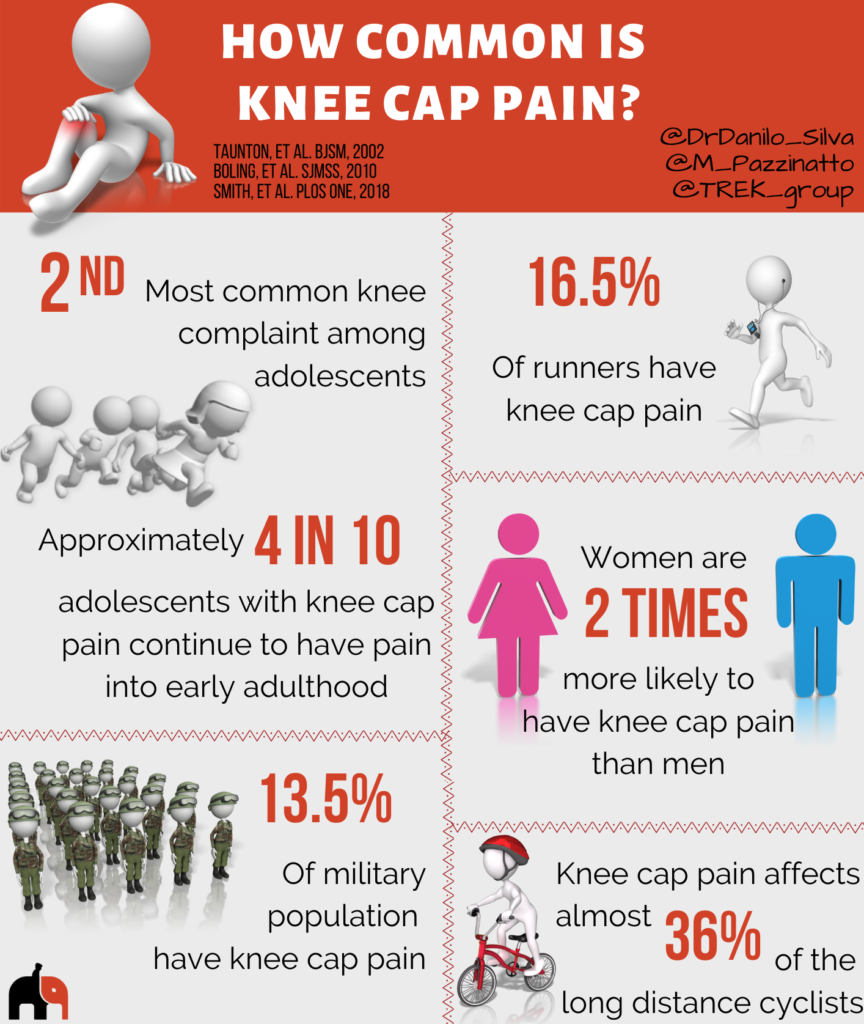

Knee cap pain is one of the most common knee conditions among adolescents, affecting up to 7% of this population. In adults, knee cap pain affects 17% of runners, and 11 to 17% of the general population.

Knee cap pain is two times more likely to affect women than men.

Supporting articles

Boling 2010. Gender differences in the incidence and prevalence of patellofemoral pain syndrome.

Smith 2018. Incidence and prevalence of patellofemoral pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Taunton 2002. A retrospective case-control analysis of 2002 running injuries.

Although knee cap pain has traditionally been viewed as self-limiting, the chronic knee pain might persist in 40% of patients after 1-year and up to 91% of patients after 18 years.

In another study 57% of the patients reported unfavourable recovery at 5 to 8 years after treatment.

However, knee cap pain treatments are effective at short-term. Thus, key factors for having a long-term sustained recovery are:

- Keep doing the exercise you learned during exercise programs

- Manage your load. Avoiding ‘too much too soon’

Supporting articles

Collins 2013. Prognostic factors for patellofemoral pain: a multicentre observational analysis.

Sandow 1985. The natural history of anterior knee pain in adolescents.

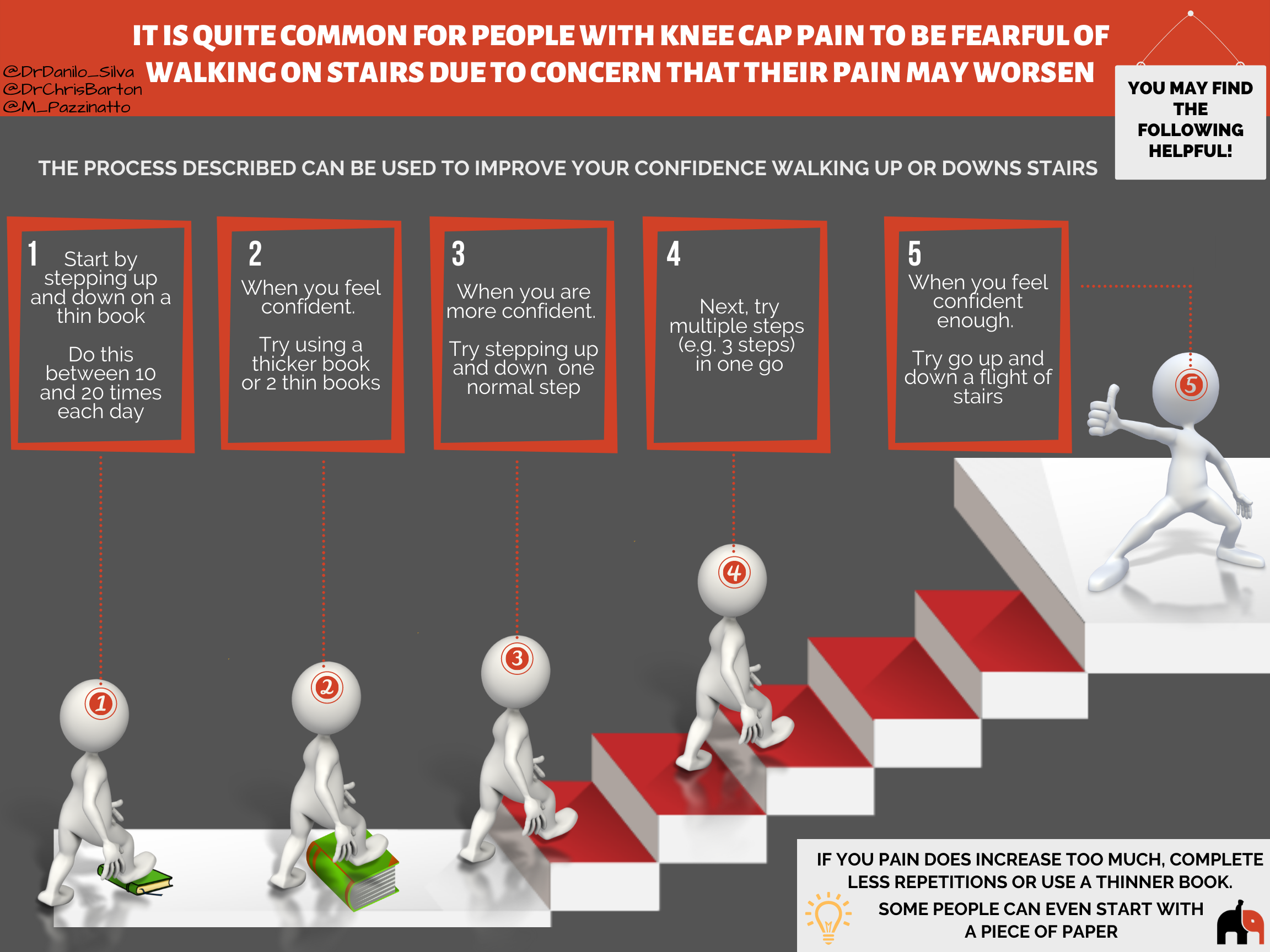

Fear of movement may exist in patients with knee cap pain. However, the most recommended intervention for knee cap pain is exercise, passive treatments are not likely to help.

Despite being quite common for patients with knee cap pain to be fearful of some movements (e.g. running, jumping and walking on stairs). Some studies report that reductions in fear of movement are related with reductions in the level of knee pain. Therefore, it is highly recommended for patients to keep doing all daily activities alongside the exercise program.

If you are not so confident to walking on stairs at the moment, you may find the following infographic helpful.

Supporting articles

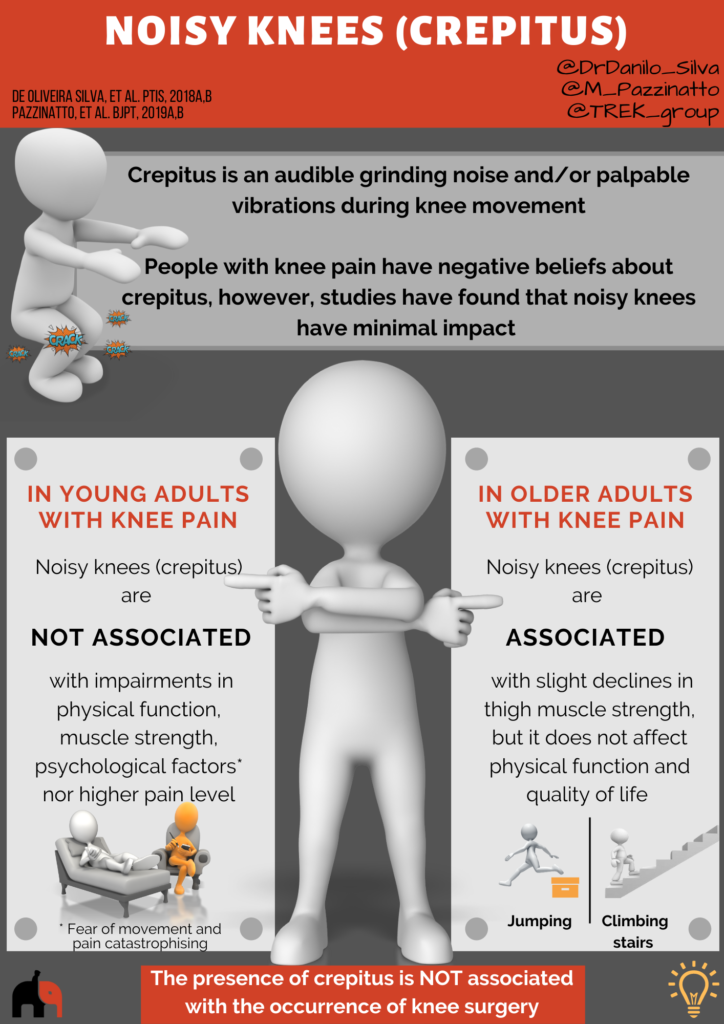

Knee crepitus or noisy knee is a common complain/concern of people with knee cap pain. We don’t know what causes the noise on the knees. But, recent data show that people with knee cap pain who have noisy knees have similar levels of pain, function, fear of movement and knee strength compared to those who don’t have noisy knees. In other words, if you have knee cap pain and a noisy knee, it doesn’t mean your condition is worse than those who have knee cap pain and no noisy knee.

Additionally, a previous study investigated 250 asymptomatic knees (knees with no pain) and found that 99% of people had knee crepitus.

Supporting articles

Physical activity is excellent, but, do you know that doing ‘too much, too soon’ may be a key reason you develop or continue to have knee cap pain?

If you are not sensible, other things may not help to manage your pain. That’s why managing load is very important.

Take a look at the short video below to get some tips on how you can manage your physical activity load (it’s less than two mins)!

Why do I need to be sensible with how much exercise I do?

The exact reason why people develop knee cap pain is unclear. However, experts around the world tend agree that doing ‘too much, too soon’ in relation to exercise may be a key reason.

There seems to be a spike in the number of people with knee cap pain following rapid increases to how much exercise you do – e.g. basic military training or ‘start to run’ programs (e.g. couch to 5KTM).

In ‘start to run’ programs it can be as high as 17%.

There are no specific rules on how much exercise you should complete in order to avoid developing knee cap pain. It is also not clear exactly how quickly to increase exercise when returning to sports and other activities if you are recovering from knee cap pain.

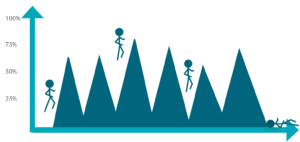

The most sensible option is to monitor your pain levels during and after exercise. Experts frequently recommend that if you have a large increase in pain, or pain stays increased for more than 24 hours after exercise, you may be doing ‘too much, too soon’.

Further guidance on how much exercise you should do and how quickly to increase it can be provided by your physiotherapist.

The following graphs taken from the education leaflet titled ‘Managing My Patellofemoral Pain’ provide a great visualisation to guide you on returning to exercise.

Supporting articles

Barton 2016. ‘Managing My Patellofemoral Pain’: the creation of an education leaflet for patients.